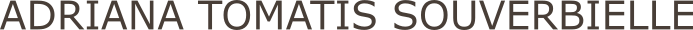

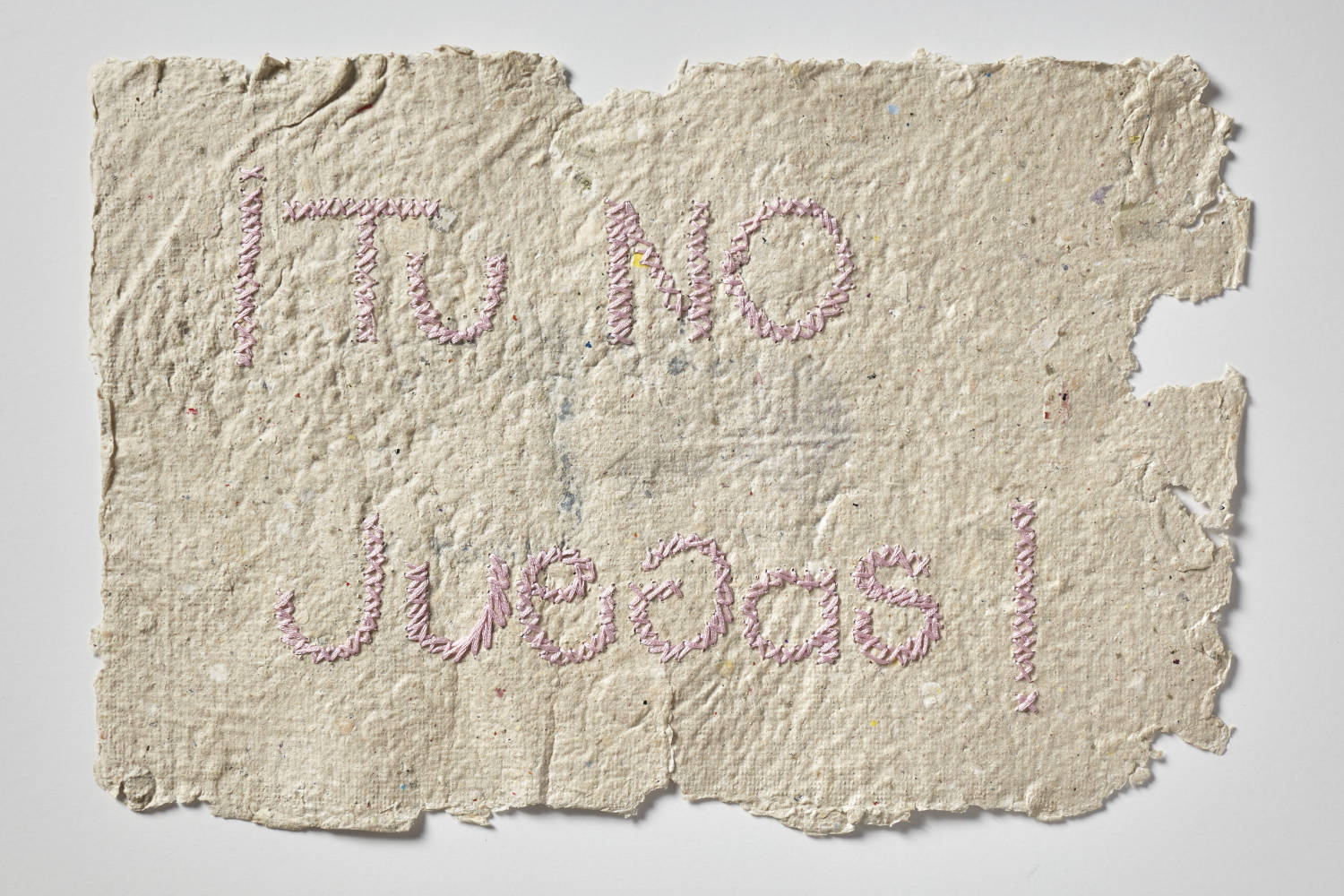

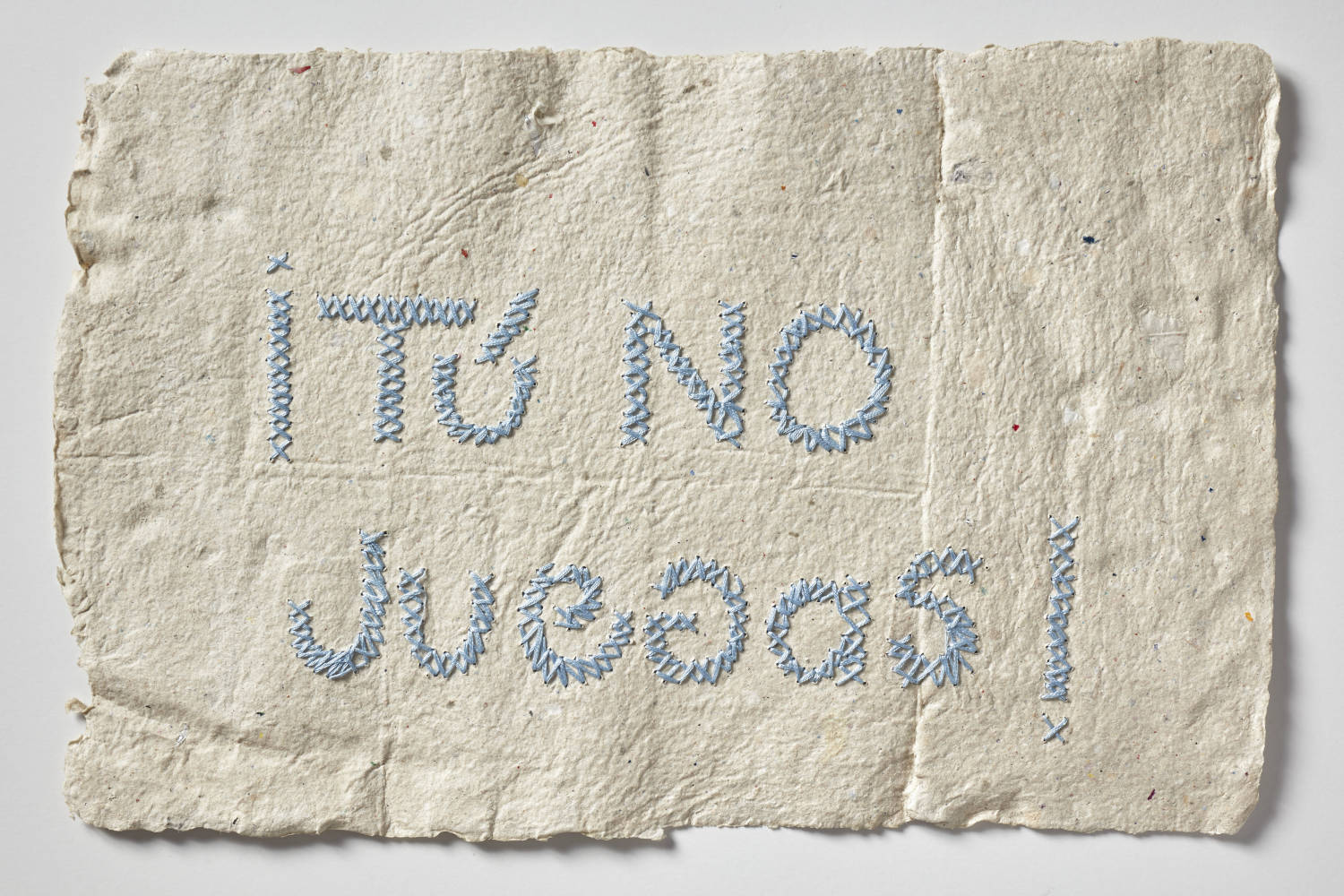

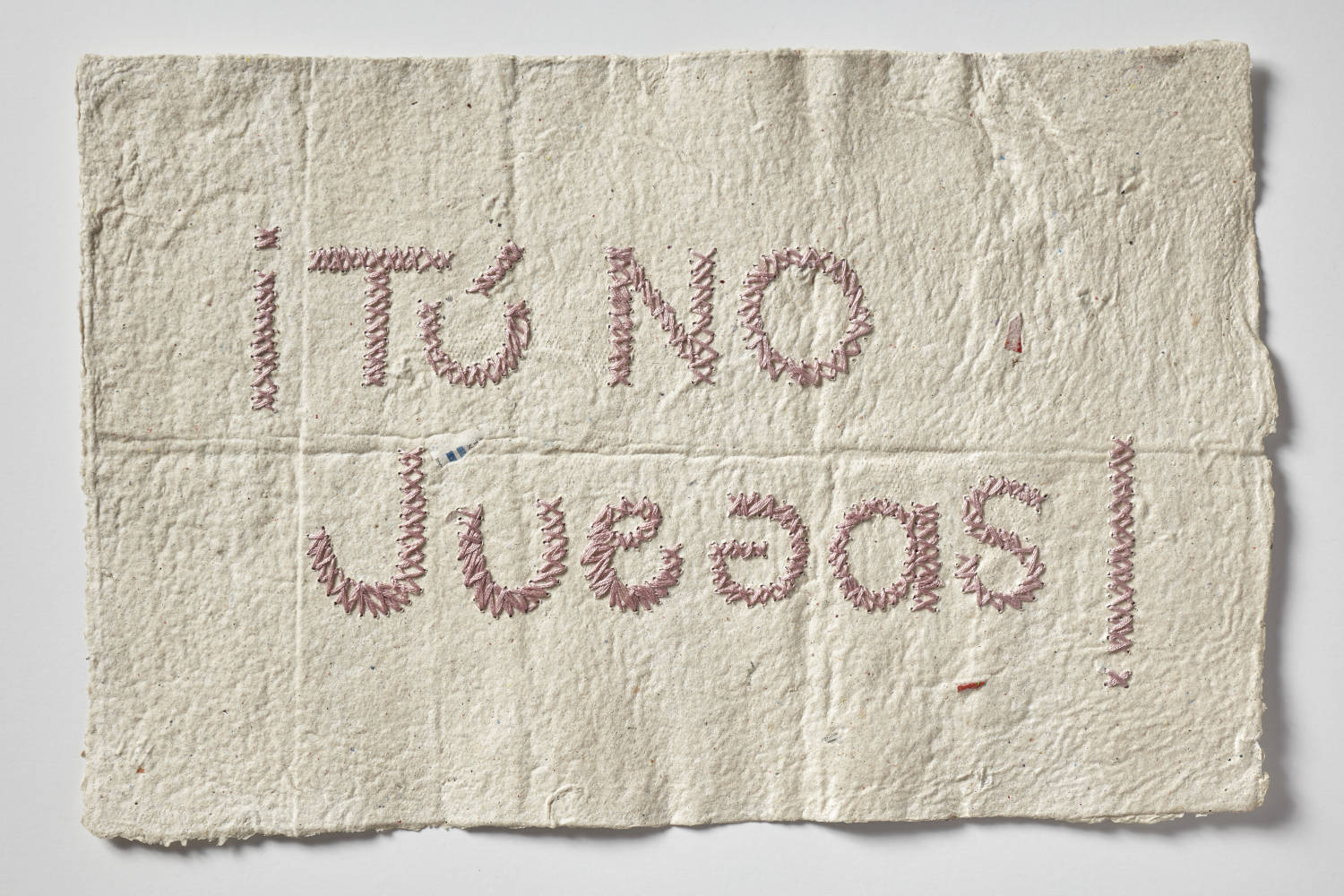

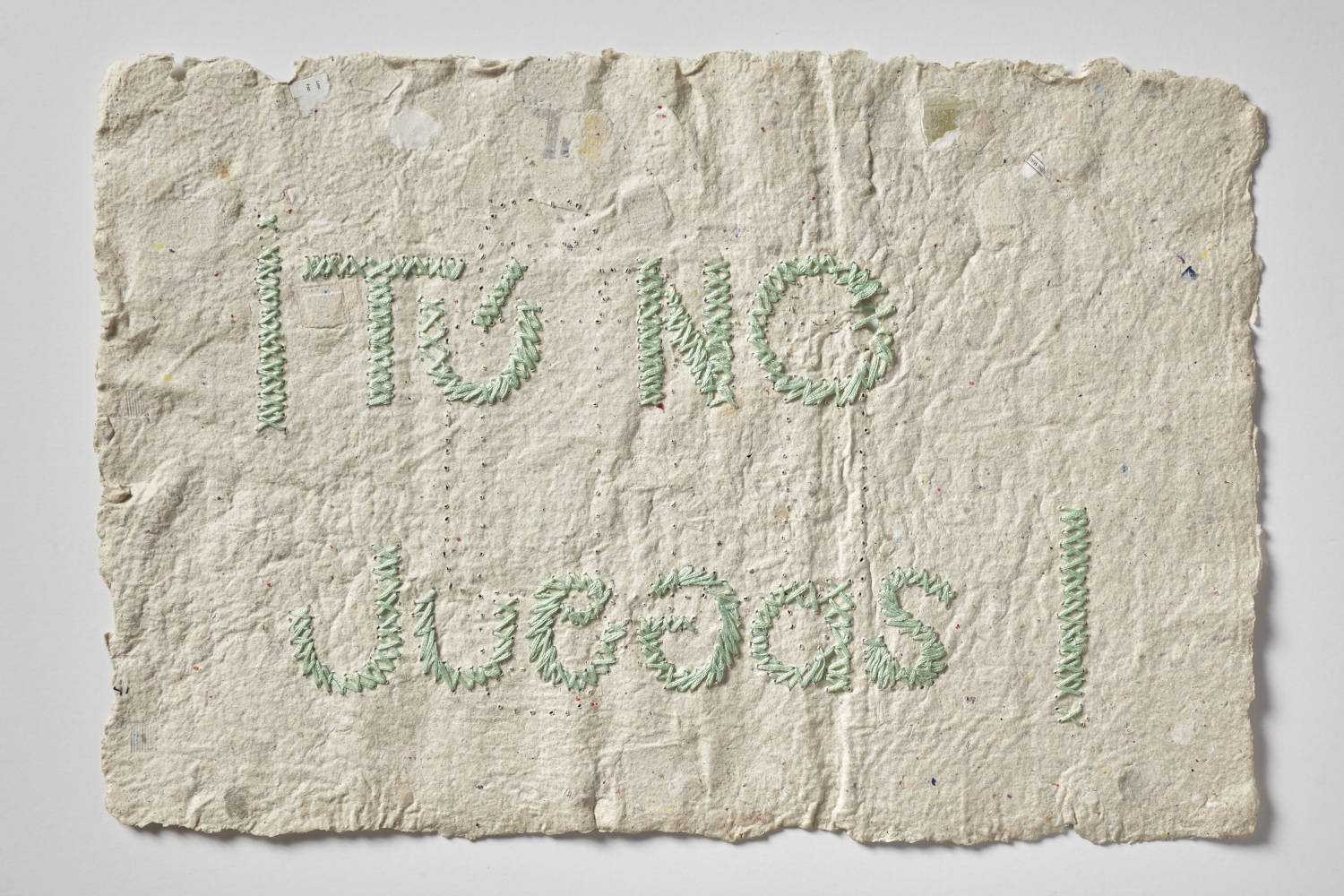

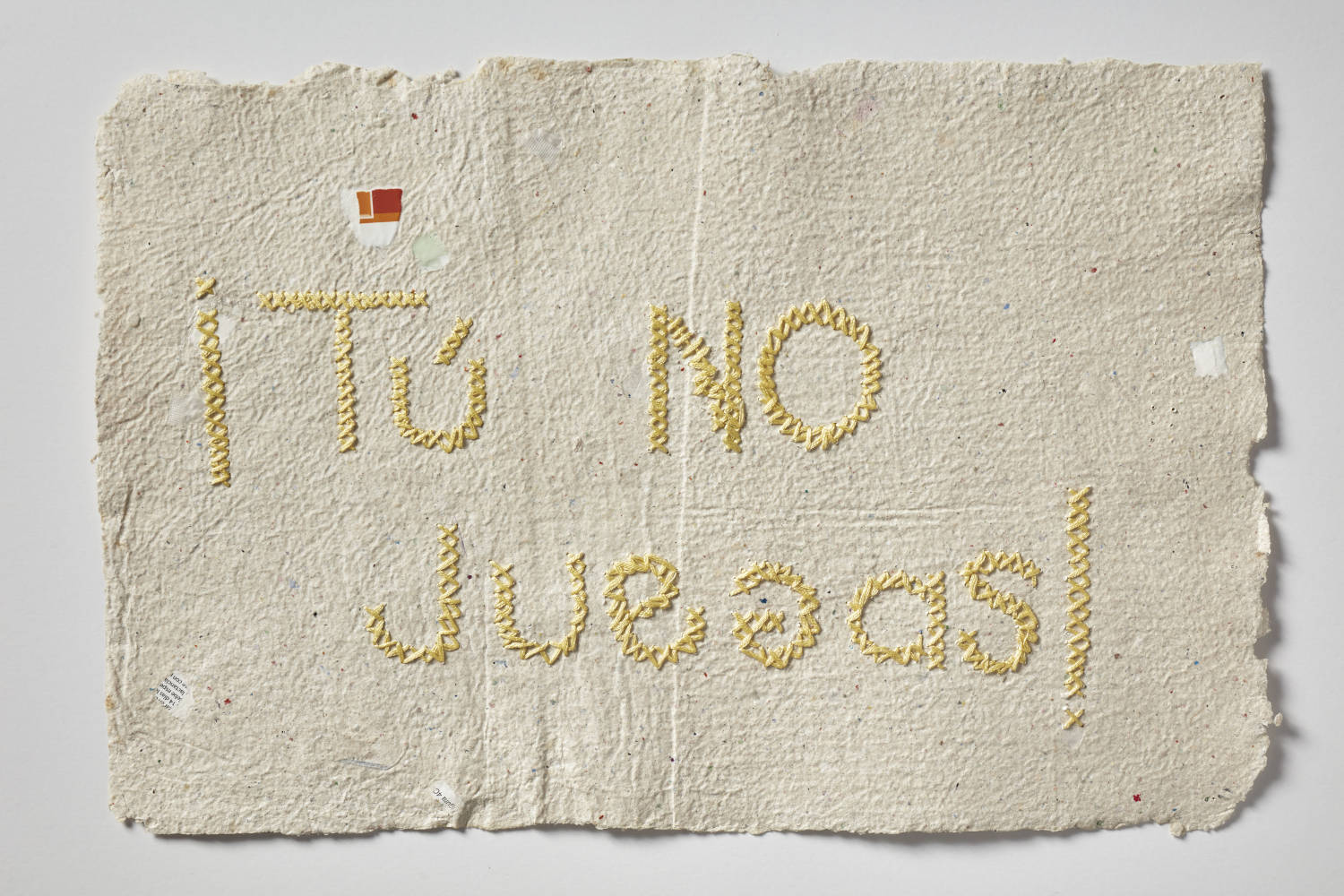

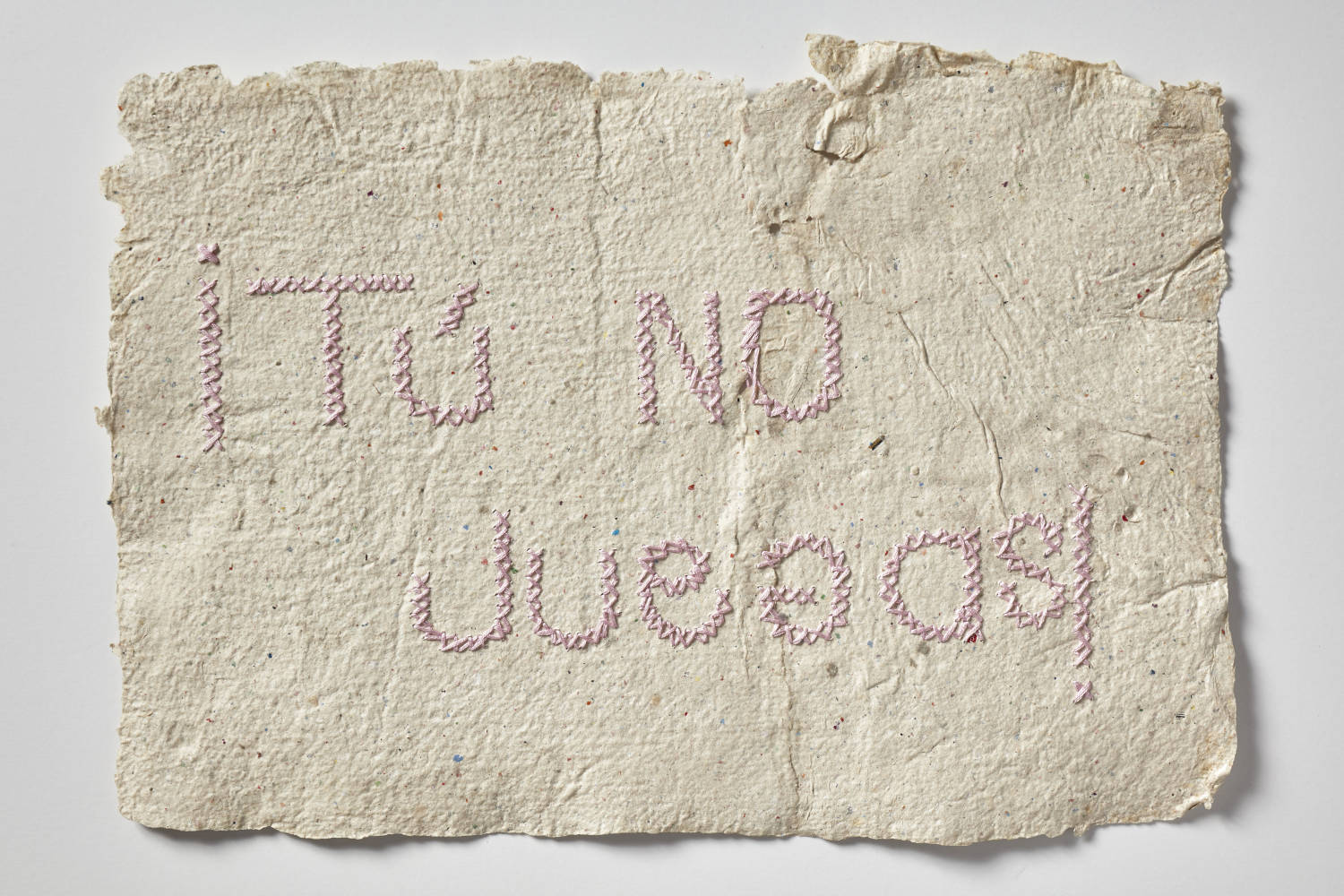

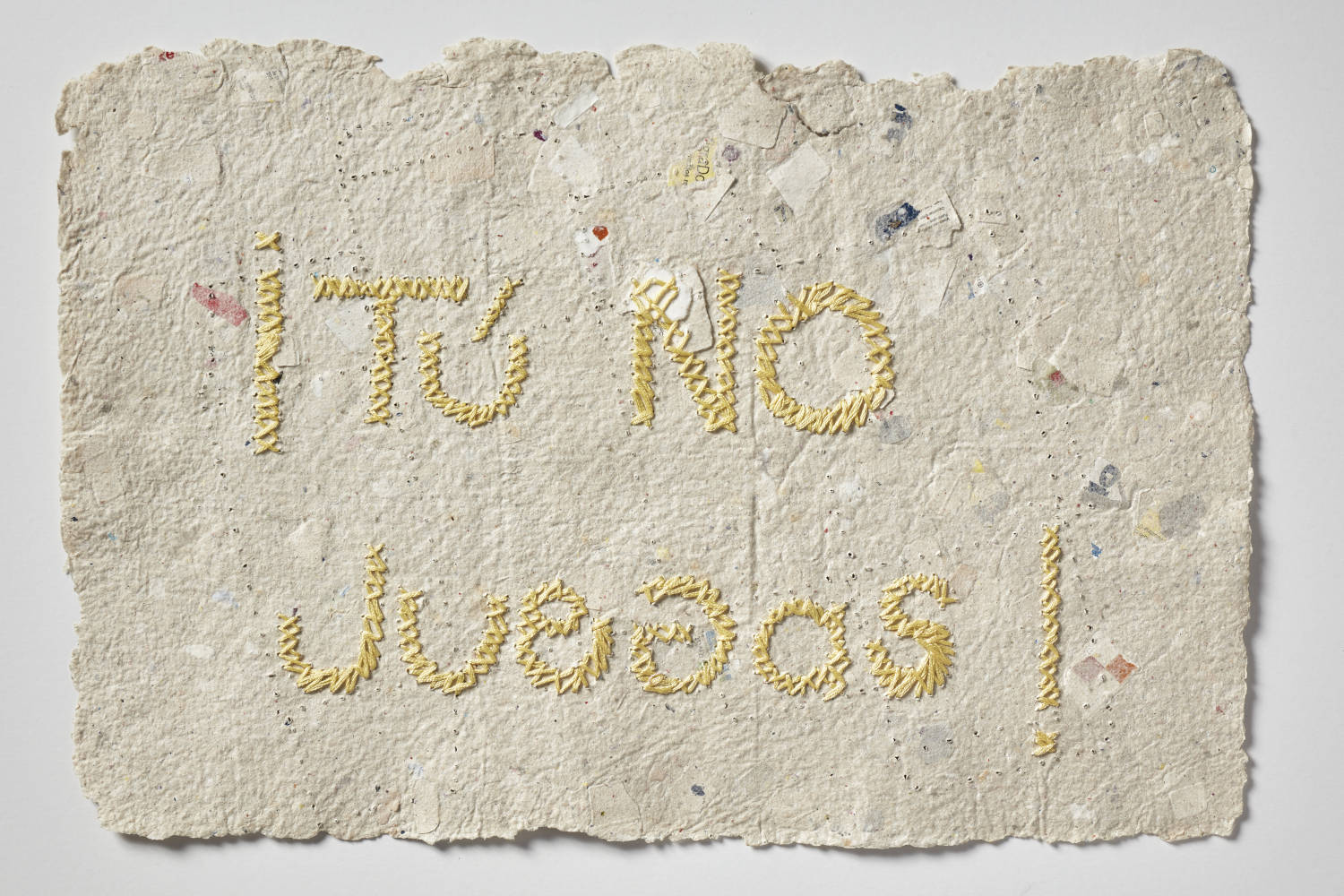

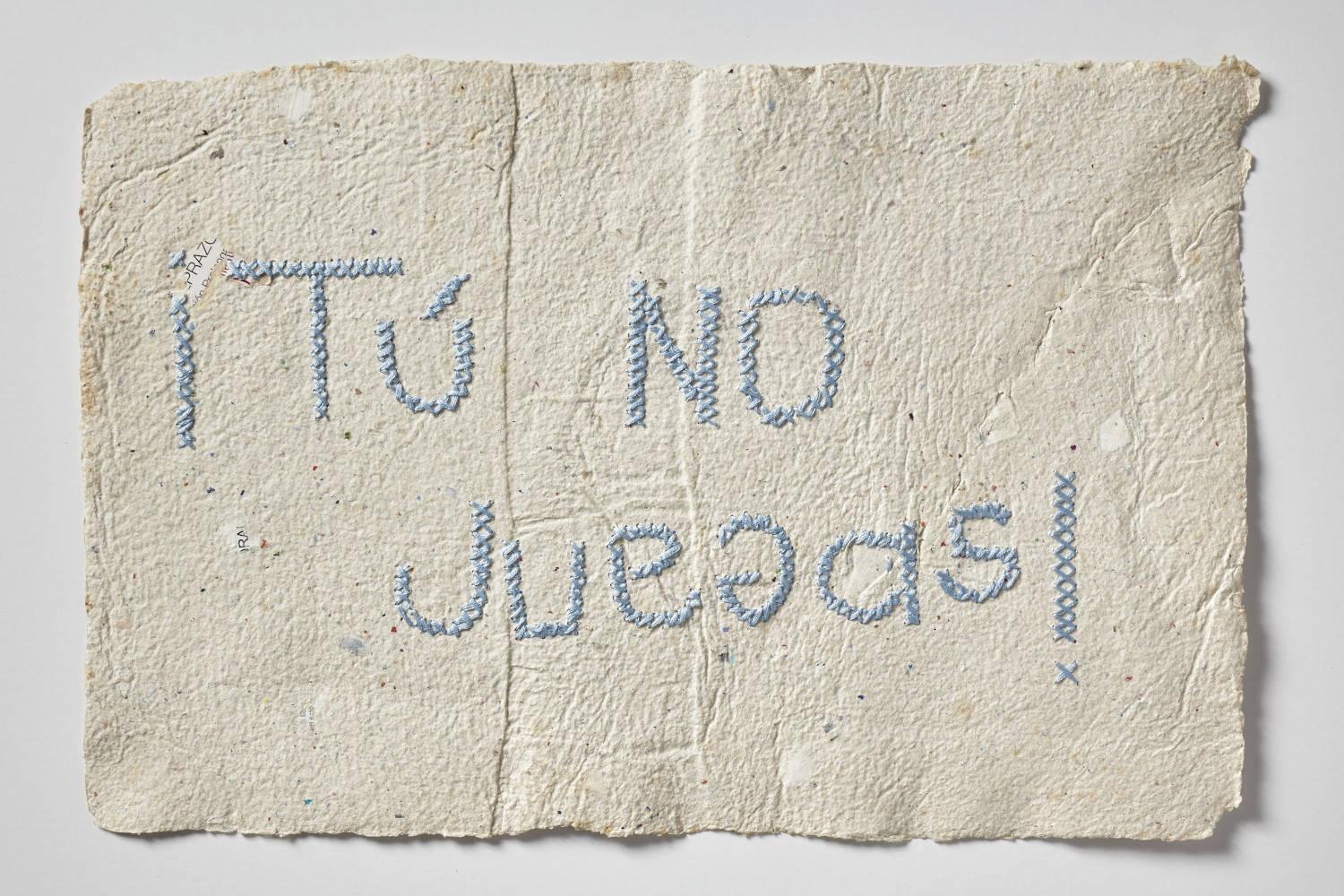

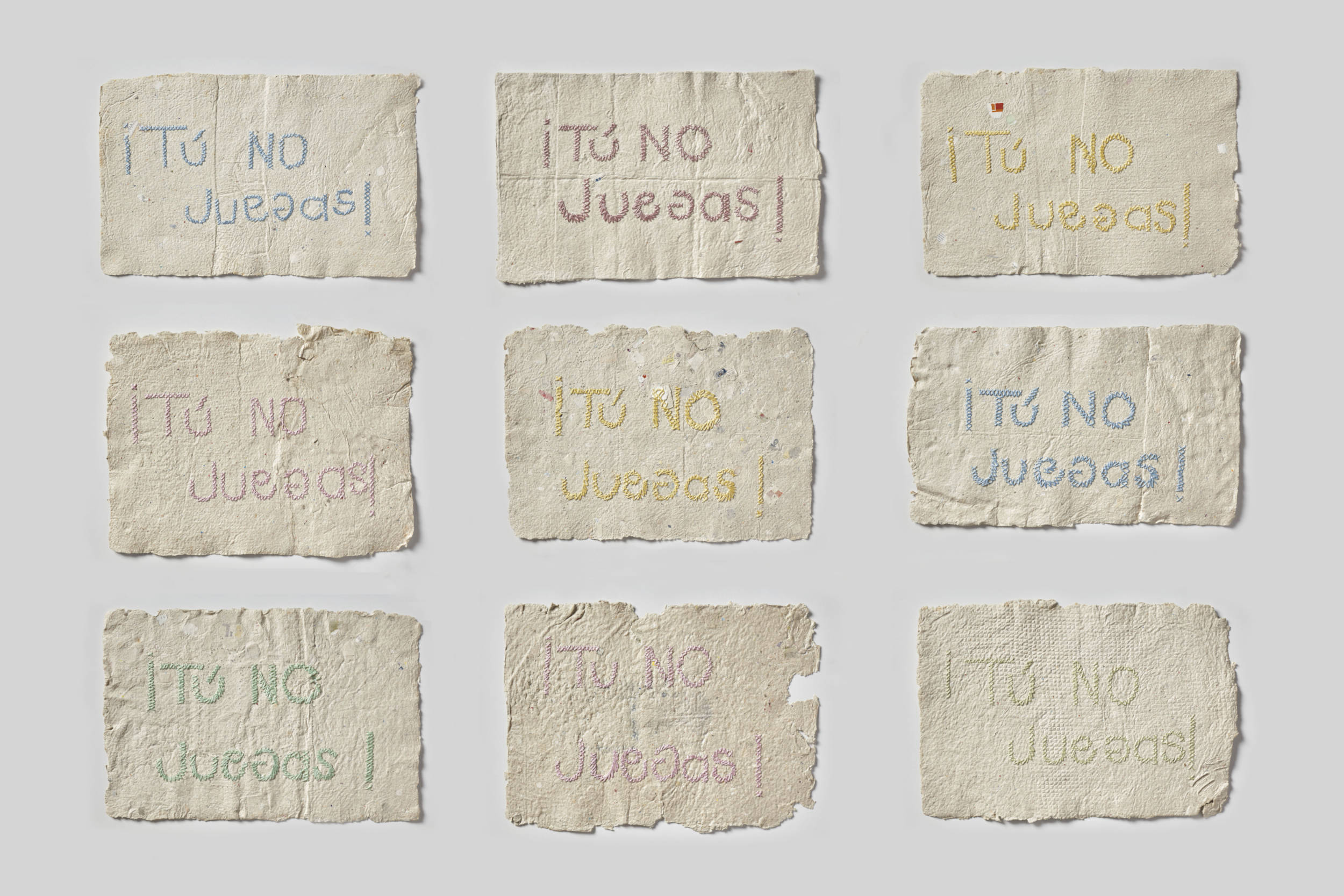

Papel reciclado e hilo de algodón. Serie de 9 piezas, (29 x 40,5 cm) 2017 – 2019

Recycled paper and cotton thread

9 pieces series (29 x 40.5 cm)

2017-2019

The literal translation of the Spanish phrase “¡Tú no juegas!” would be “You don’t play”, but maybe a correct translation could be “you are not playing with us!”, a phrase usually used by kids to bully other kids, an outsider, that may want to join an already formed group. This phrase is usually used by the leader of the group to demonstrate his power over the others.

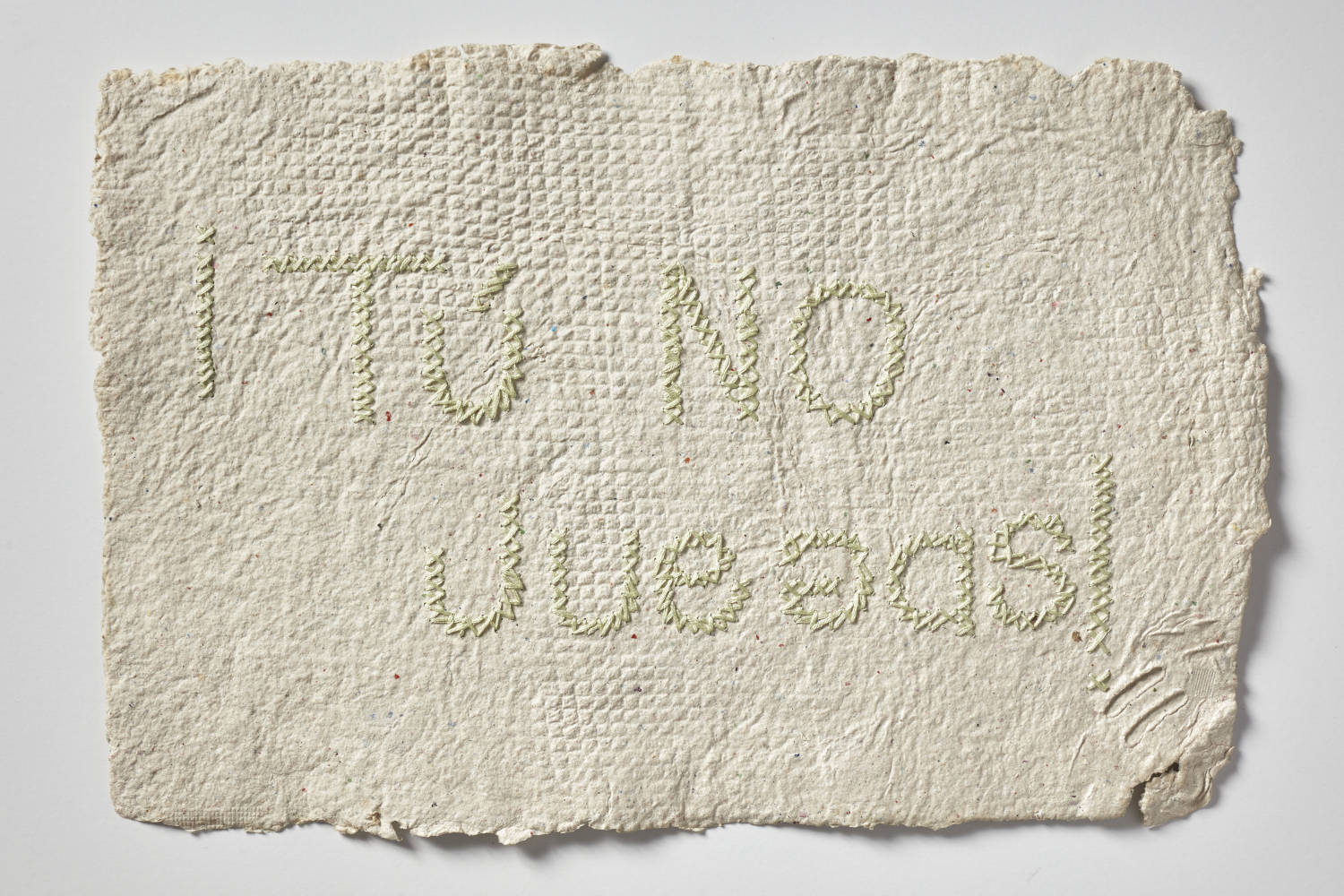

This work consists of nine handmade papers stich with the phrase “¡Tú no juegas!” in a classic cross point stitching, in four pastels colors, commonly used in baby clothing and decorations (light pink, light blue, light yellow, and light green). And even though I´m not allow to play, I kind still do just by playing with the letters on the phrase.

These handmade papers are recycled from the cartons of psychotropic medicines that I myself have to take, and that I had been collecting for the last 9 years. I brought these recycled papers with me from Perú, from an old project to represented a past stage in my creative process before coming to Italy for my postgraduate studies. The papers are rough, almost childish, showing rests of the original cartons of the medicine as a clue for the spectator. And the new part, the stitching, represents a hard part in my passage through Milano: Life in a new city, very far away from home, with a new language, that I still don’t speak very well, a big gab difference between me and my classmates, a small hint of racism, and what I call old shadows of colonialism, as myself the obvious outsider. The use of stitching a typical diminish feminine labor is almost performative as the needle goes through the paper reopening wounds on an already glued surface.